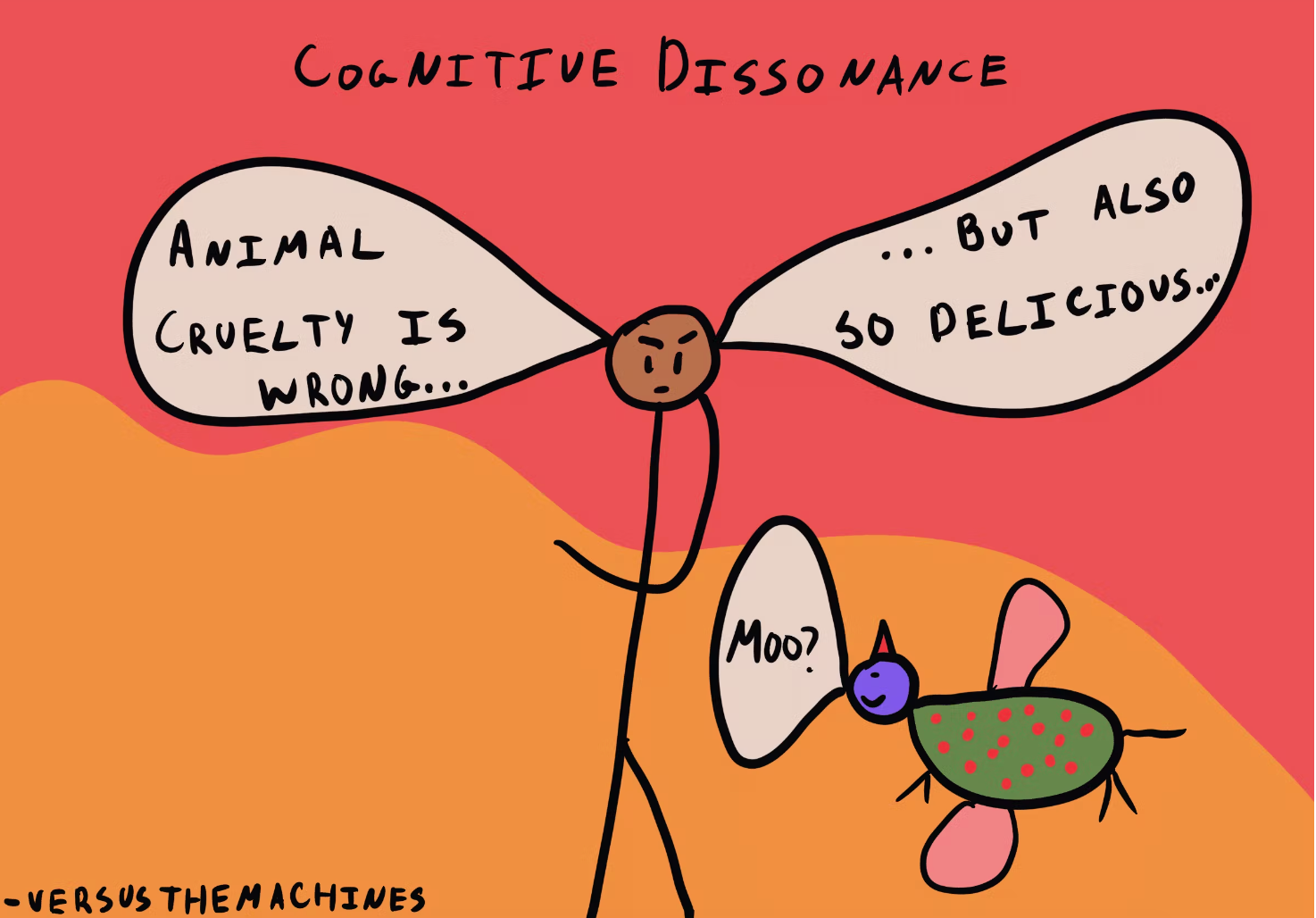

[I took the fun image above from The Decision Lab's article about cognitive dissonance. I realize that thinking about meat and animal cruelty is an easy example for me to use as a person who doesn't eat cow, so I apologize if the comic hits closer to home for you. I think we can all agree that the pink/orange and cow/fly combinations are fun.]

I wrote a post called "Why Yes...And" in May of last year. Feel free to read it now if you haven't already or if you've forgotten what it was about, but please don't forget to come back to today's post, which employs similar wording to make a very different point.

This academic year, I took on a new job that requires me, for the first time in my long teaching career, to handle the discipline side of education. (I realize that sentence might seem silly to people who understand and/or care about etymology, as discipline comes from the Latin word that means instruction or knowledge, so in its meaning, there's not a difference between discipline and education.) In the past, I've accompanied a few advisees to Discipline Committee meetings, shepherding them through the process of learning from their bad choices. This year, I've been the one steering the ship after students do things they certainly regret getting caught having done. I value the process and hope that every student who goes through the system learns from each step: getting caught, taking ownership, writing to explain what happened, answering questions from their peers and from faculty, and receiving a response.

I wrote in a recent post that several of the children who have done icky things deny holding the bad values their actions imply. And it's right, I don't think they are bad people. At the same time, they've done bad things.

And this source of cognitive dissonance is what I wanted to write my post about. I'm guessing these children and I are not the only people who have done things of which we're not proud. At the same time, I think it's important for every human to feel fundamentally good. It's hard, often, to hold those two thoughts at the same time, but they can both be true:

- I have done bad things.

- I am not a bad person.

The way we can reconcile these opposites is by remembering that neither is the whole picture. Think, now, of the infinite list of also-truths about ourselves:

- I have done good things.

- I am learning about how to behave.

- I sometimes act too quickly.

- I don't know all of my options.

- I want to be liked.

- I want to be respected.

- I like feeling good in the moment.

- I value my future.

I won't write out more here, but I hope you can already see that there are so many facts about all of us. Focusing on two that seem to contradict each other makes sense only if we keep our view problematically narrow. As soon as we open ourselves up to consider the many complexities that are accurate about all of us, we must acknowledge the same nuances and multiplicities about others.

In explaining to parents what their children have done, I find myself repeating the pair of facts I wrote above. I don't know if it helps the parents reconcile the totally unexpected actions of their children, but I hope it helps them to remember that one fact is never the full story.

When are moments in your life you've had to grapple with cognitive dissonance? How did you come to terms with seemingly opposite beliefs? Please share your thoughts in the comments.

Perhaps one of the many values of learning a bit of contemporary physics is that light, so prevalent in our lives, is a particle, is a wave. Or thinking of adopting Schrödinger’s cat as a pet. Or the joys of language: This statement is false.

I both love these both/and examples and find them all confusingly impossible. Thanks!